During the COVID-19 crisis, we have seen the emergence of contract tracing (or more accurately, proximity tracing) tools as a means to limit the virus spreading. While some view these technologies as a solution to the lockdown, others are more cautious, seeing them as invasive to our privacy, likely to cause new kinds of discrimination or stigmatisation, and a danger to our civil liberties.

It is important that evangelicals are aware of the potential impacts of these technologies. With the lockdown now easing the deployment of this technology may appear innocuous or a non-starter. However, having already spent £11.8m million trying to develop its own app, on 18 June 2020, the UK Government announced a change in its approach and is now seeking to use the Google and Apple Application Programming Interface (API).

What’s it all about?

In April 2020 Google and Apple formed a joint collaboration to develop technology for a mobile phone app to help governments to track the origins and spread of virus outbreaks. This contact tracing is done with Bluetooth-enabled smart devices based on Android or iOS operating systems.

The premise being that the longer a person’s device in close proximity with another person’s device, the greater the risk of contracting COVID-19. The intention being to help notify those ‘at risk’ (known or unknown to us) faster than manual contact tracing efforts based on the proximity encounters of their device. Some governments (like the UK’s) want to also use data gleaned from the app for public health research purposes to better prepare for future pandemics.

What’s the difference between a centralised and decentralised app?

Whether it is ‘centralised’ or ‘decentralised’, any proximity tracing tool will have benefits and risks. A centralised app means the app is managed and data stored centrally from a centralised server. In contrast, a decentralised app is mostly managed from the device but does upload the Bluetooth identifying encrypted codes (IDs) transmitted from the device of the infected person. No information is stored centrally.

What is needed for the contact tracing app to work?

The app would be effective:

- If there is an efficient programme of testing for the virus.

- If it helps to support manual contact tracing methods (such as health professionals enquiring about your recent contacts and activities where you could have come into contact with people).

- If enough people in England, Wales, Scotland and Northern Ireland:

- had a Bluetooth-enabled device;

- downloaded the app on to that device;

- carried that device with them all the time;

- the device were not shared or stolen;

- people self-isolated when symptoms appeared; and

- adhered to the instructions given by the app.

- If financial support was available to those who have to self-isolate or quarantine.

- If the app could communicate with the COVID-19 apps of other countries. For example, if it could still function for people who travel across borders (i.e. between Northern Ireland and the Republic of Ireland or between the UK and France).

What are the risks and concerns about having a contact tracing app?

Effectiveness: The app won’t be much use if only one person on a crowded train has downloaded it. It will only be as effective as the coverage of the people carrying smart devices, and it is unclear whether the UK will ever meet the right threshold for this. Also, the app will likely be ineffective for those who cannot carry a personal smart device at work due to the nature of their job

Disruption: As the app relies on self-declaration, the concern is that where someone falsely declares themselves as infected with COVID-19, others get alerted and instructed to self-isolate. This causes unnecessary disruption. Conversely, when someone is infected but doesn’t declare themselves as infected, they will continue to spread without alerting others to the risk, being disruptive to the tool.

Unreliable results: To be classified as ‘at risk’, the smart device must have met a threshold risk calculation based on how long someone has been near an infected person’s device – and how close they were to that person. To get the risk calculation right, other factors will need to be taken into account, including whether the infected person’s phone reliably picked up our Bluetooth signal within the correct two-meter radius. (For example, it would not be considered reliable if the Bluetooth signal were broadcast and received through a thin pre-fabricated wall of an 1960s tower block where each of the smart devices happened to be either side of the wall in a separate person’s flat.)

Malicious use: Whether it is to disrupt the system, create hotspots, falsely identify someone as ‘at risk’, to intercept Bluetooth transmitted IDs between devices, or to try and reidentify those who caused the alert to be generated, we are likely to see an increase in the technological mischief.

Re-identification: The apps try to preserve privacy through anonymising and encrypting data, but if a person felt grief or anger towards the person who infected them, they might actively take measures to try and discover who it was. If we have limited contact with others, it will be easy to identify who might have infected us. Others unknown to us in a supermarket or on the street will be less so, but it may be possible to ascertain from CCTV footage, records held on the device or from notification alerts the occurrence of the proximity encounter.

Stigma and discrimination: The nature of our work and social relationships may change. Before we meet in person, friends, acquaintances, or those we trade with may ask us to actively use an app. It may even become a condition of returning to work, to availing of health insurance, or to travel. This will likely result in huge social pressure to conform to downloading the app. Also, if people fail to adhere to social distancing or lockdown measures are reactivated following a second spike, people may be increasingly willing to accept any measures for life to return to ‘normal’.

Digital and social divide: A largescale technological response to the pandemic risks a digital and social divide effectively creating a digital underclass. Large swathes of the population comprised of those that can’t access or don’t have devices would be left behind. Those likely to be relegated to a form of second-class citizenship would include the poor, the young, the old, and the vulnerable.

Mission creep: Without clearly defined time-limits and safeguards, the app for tracing could be used beyond what is strictly necessary for containment of COVID-19. This could include the monitoring of social interaction data and location tracking, which ultimately represents an opportunity for more surveillance whether by governments or by private companies.

What next?

While it is unlikely that the Government will abandon plans for an app, it is likely that there will be a delay in its deployment in the UK. During this delay it is possible that the private sector may take the opportunity to take technological measures of its own, for the health and safety of its employees and customers.

Our ‘new normal’ may involve body thermo-scanners being deployed on entry to buildings, public transport and airports; our employers requiring evidence of being virus free, or having had the vaccination, before we return to work or shared workspaces; restaurants, pubs and cafès requiring contact details for COVID-19 follow-up on departure; and smart watches, contactless RFID cards or wearables being deployed for traceability (radio frequency identification is a technology used in contactless cards and devices for tracking/reading at a distance). It may also involve an increasing demand for health information about ourselves, family, partner or those with whom we ‘bubble’, other than by the NHS. This will have an impact on how society lives and behaves, with or without the app.

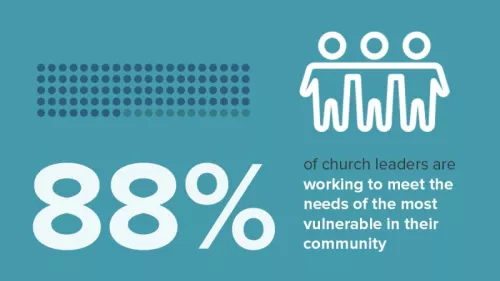

The global pandemic has neither surprised nor fazed God. In the midst of this great shaking the church is worshipping online, serving its communities and proclaiming the gospel. God is clearly doing a new thing (Isaiah 43:19), increasing opportunities for the church to mobilise and impact society for good.

One thing is certain, things are changing fast. It is important for God’s people to be aware, not only of the factors that are driving the introduction of these new technologies, but also of their possible unintended consequences – not least their potentially profound impact upon civil liberties and human rights

While we neither need to be afraid (Matthew 10:28) or indulge in conspiracy theories (Isaiah 8:11 – 17), we also should not be ignorant of the nature of these technological developments. We need to understand them in order to have an informed and intelligent voice about them.

This is a time for wisdom and discernment – for understanding the times that we are living in and for watching, praying and speaking out when needed. The Evangelical Alliance is committed to keeping you updated on these technological developments.

Find out more

- NHS COVID19 App Isle of Wight trial website: https://covid19.nhs.uk/

- BBC explainer about how the App works: https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/technology-52355028

- British Institute of Human Rights explainer about COVID19 Apps and Human Rights: https://www.bihr.org.uk/explainer-contact-tracing-app

- Announcement that UK doing a U-Turn from its own App to using Google and Apple API: https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/technology-53095336

- Data protection considerations on workplace testing: https://www.scl.org/articles/11946-workplace-testing-for-coronavirus-data-protection-considerations-can-t-be-factored-in-overnight

- Information Commissioners Office published guidance for organisations on testing to help with the recovery and guidance on what your rights are in the coronavirus recovery

- UK Equality and Human Rights Commission Guidance for employers: https://www.equalityhumanrights.com/en/advice-and-guidance/coronavirus-covid-19-guidance-employers

- UK Joint Human Rights Committee report on contact tracing Apps: https://www.parliament.uk/business/committees/committees-a-z/joint-select/human-rights-committee/news-parliament-2017/covid-19-contact-tracing-app-report-published-19 – 21/

- An international comparison of Covid19 Apps by Privacy International: https://privacyinternational.org/examples/apps-and-covid-19

- An international perspective of COVID19 Apps by the Human Technology Foundation: http://optictechnology.org/index.php/en/news-en/241-technology-governance-during-crises

This resource was produced with the help of Patricia Shaw, Founder of the Homo Responsiblis Initiative – a Christian think tank of experts in artificial intelligence and digital technologies with a Christian worldview perspective.

For more information please visit: https://www.europeanea.org/patricia-shaw-founder-of-the-homo-responsiblis-initiative-think-action-tank-aims-to-mobilize-christians-in-the-sphere-of-artificial-intelligence/ on Twitter: @ResponsibleHum6 and on LinkedIN.