What is extremism and how best can we protect ourselves, our freedoms and our society from it?

This consultation closed on Thursday, 31 January 2019.

We’re here to help you to have your say on these vital issues.

Last year, the Government established a Commission for Countering Extremism which was tasked with defining ‘extremism’ and proposing responses to it. Now the Commission wants to hear from you about extremism in England and Wales.

For a number of years, the Government has been trying to present and pass laws to counter extremism. But this has been fraught with difficulty, not least because of the challenges around a workable definition of extremism itself. Under its lead commissioner, Sara Khan, the Commission for Countering Extremism has been seeking to gather evidence that could resolve this issue.

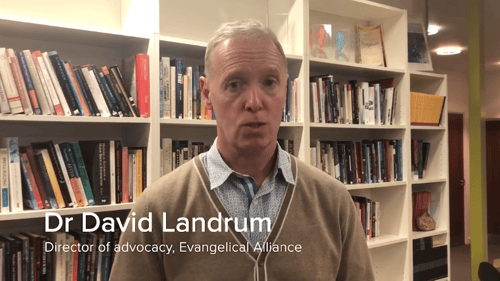

We fully support moves to tackle radicalisation and terrorism, but the Evangelical Alliance has raised serious concerns around the Government’s suggested counter-extremism policy. We believe that a vague definition of extremism could be used to undermine some of the very freedoms the Government should seeking to protect, especially those freedom of thought, expression and speech. We are concerned that poorly considered legislation could have far reaching repercussions, and may even be used against those who hold conservative religious views or opinions which differ from current social norms, even if they do not incite violence.

Our public policy team will be responding to this consultation, but this is also your opportunity to give your views on defining extremism, who the victims of extremism are, and how we can best respond.

We have selected some of the key questions in the consultation, and offered suggestions to help you think about your answers.

Please respond in your own words. Visit this https://www.gov.uk/government/consultations/extremism-in-england-and-wales-call-for-evidence) and click “Respond Online”.

Questions on defining extremism

1) Can you describe extremism?

Points you may want to bear in mind in your answer:

- Violence, crime and terrorism are covered by numerous specific criminal offences. However, “extremism” can be stretched to cover non-violent beliefs, and so is a much more subjective and vague concept. Anyone can accuse anyone else of being an extremist.

- In a 2017 ComRes poll commissioned by the Evangelical Alliance and others, more than half of the public (54 per cent) thought using the word ‘extreme’ is not helpful in social and political discussion.

- In addition, in the same survey the public disagreed widely on what could be defined as “extreme”, once violence was removed from the picture. Nearly four in 10 (39 per cent) considered it extreme to believe that climate change is an important global problem made worse by human behaviours. Meanwhile, three out of 10 (30 per cent) thought it was extreme to believe the UK should remain in the EU, whereas 36 per cent said it was extreme to believe the UK should leave.

2) How helpful is the following definition of extremism?

“Extremism is the vocal or active opposition to our fundamental values, including democracy, the rule of law, individual liberty and the mutual respect and tolerance of different faiths and beliefs. We also regard calls for the death of members of our armed forces as extremist”. (HM Government Counter-Extremism Strategy, 2015)

Points you may want to bear in mind in your answer:

- In 2016 the Joint Committee on Human Rights strongly criticised the Government on this definition of extremism saying: “The Government gave us no impression of having a coherent or sufficiently precise definition of either ‘non-violent extremism’ or ‘British values’. There needs to be certainty in the law so that those who are asked to comply with and enforce the law know what behaviour is and is not lawful.” (Paragraph 108 of this report: http://www.publications.parliament.uk/pa/jt201617/jtselect/jtrights/105/105.pdf)

- The Archbishop of Canterbury Justin Welby said that he could be seen as an extremist, according to one interpretation of the Government’s definition: https://www.christian.org.uk/news/justin-welby-im-extremist-according-govts-definition/.

- The definition does not distinguish between respect for people and respect for their beliefs. It is possible to respect a person but not respect their beliefs.

- Defining certain non-violent beliefs as extremist may encourage authoritarian governments around the world to criminalise dissent and minority views. See this article by Jane Kinninmont for examples: https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2016/sep/23/britain-extremism-global-effects. To avoid this, a helpful definition of extremism must surely be clear about what extremism is not, as well as what it is.

Questions on victims and perpetrators of extremism

5a.) Have you witnessed anything you would regard as extremist happening in your local area, elsewhere in the country or online?

5b.) If you said ‘yes’, what type(s) of extremism have you witnessed? Please select any that apply from the following options that were suggested to us during our engagement and from our ongoing research.

7a.) From the following list, which are the three groups you believe are most at risk of harm caused by extremism?

7b.) What is the main reason for your response? Please write your answer here (100-word limit)

You may notice as you read the suggested options that questions 5 and 7 exhibit a concerning bias against religious communities, which should be pointed out to the Commission. Question 5b) asks about who is likely to be a perpetrator of extremism, and gives you a list of different religions, as well as other things, which might give rise to extremism. However, when question 7a) lists victims of extremism, it refers to “non-religious people”. But if extremism can mean any disrespect or intolerance towards those of different faiths or beliefs, then surely non-religious people can be as prone to extremism as religious groups. Describing non-religious people as victims but not perpetrators is bound to make some people wonder whether the Commission really does see religious believers as problems not partners in the fight against extremism.

Questions on responding to extremism

10) Do you think more should be done to counter extremism?

Points you may want to bear in mind in your answer:

- Efforts to counter extremism should focus on existing crimes and on those inciting violence. We should therefore prioritise practical and necessary support for the police, intelligence services and the criminal justice system in investigating these crimes and prosecuting those who commit them.

- The debate around counter-extremism has led to great uncertainty among different groups about whether they will be caught up in an overly broad (and distinctly secular) definition of extremism. This has had a chilling effect on civil society – in fact one of our best defences against extremist violence and crime. The Commission should therefore seek to reassure these communities and rebuild trust with them. In particular, the Commission should seek to foster religious literacy and an understanding of deeply held religious views in government and society at all levels.

- The best defence against extremist ideas is to ensure that they can be debated freely and criticised publicly. We should therefore prioritise support for freedom of speech as a tool against extremism.

- The Commission should take the initiative in speaking up for those in fear of violence because of their religion or belief – you may wish to note especially Sara Khan’s support for offering asylum to Asia Bibi – https://www.eauk.org/news-and-views/religious-freedom-asia-bibi-and-the-home-office.

14.) What is the one thing you would give greater priority to, in our efforts to counter extremism offline and online, and why

This question gives you an opportunity to re-emphasise one of the core points you’ve made before (see for example answers to question 10 above).

So if you live in England and Wales, please respond to the consultation by following this link https://www.gov.uk/government/consultations/extremism-in-england-and-wales-call-for-evidence, before the deadline on Thursday, 31 January 2019. Again, please use your own words in your response.